The Army of the Indus and the Advance to Kabul

|

The Army of the Indus consisted of one force from Bengal in the east, and one

from Bombay in the west, of the British Army. In addition, the East India

Company raised its' own regiment, plus two regiments of Indian cavalry and

twelve regiments of Indian infantry. Of the men raised for Shah Shuja's army, no

one seems to have been very impressed with them. Speculation was that

not only were they not very committed to the Shah, but that the native

Indian troops, trained in and used to

the heat of the plains, would not fare well in Afghanistan's hilly contours and

desperately cold winter.

Calcutta's Bengal Army gathered near Ferozepore on the Sutlej river in

the Punjab in late November of 1838. G/G Auckland joined them and a few

days later met Ranjit Singh with his forces. The first meeting, at the English

camp, nearly turned in

to a riot, with the clamor of the varied musicians, over one hundred elephants

in a tiny space, and the Sikh and British officers jockeying for position. Singh

himself almost got knocked over and crushed in the melee, had not an English

officer grabbed him and literally carried the little man into the durbar

pavilion. Later, in fact, he did trip over a cannon shell and fell flat on his

face. He was unhurt, but his ministers and elite Khalsa guard were

reportedly aghast as the spectre of their leader, prostrate before the

British guns.

The next day, the whole mob turned around and made it's way to Singh's

encampment in 110 degree heat, at a pace which one officer later described as

"a snail's gallop". The party that night was riotous, to say the

least, with wine, women and song. Miss Emily Eden, ever the archetypical

Victorian maiden aunt and fussbudget, described how she "did not particularly care

for the affair, with all those satraps in a row and those screaming girls and

crowds of long-bearded attendants and the old tyrant drinking in the

middle." The "old tyrant" was attended to by dozens of rather

comely Kashmiri dancing girls whom he loved to watch gallop by, topless,

on horses, and also by jewel-bedecked young boys to whom he turned when

age and illness made the girls not as attractive a recourse. One can

imagine the strait-laced English view of all this Oriental tomfoolery...

While still at Ferozepore, Auckland deemed that Sir Henry Fane and five

Indian regiments would stay behind as reserves. Fane then, oddly enough, resigned himself

from the army. He evidently decided that an expedition of this size, entering a

country so barren and destitute it could barely feed its' own inhabitants much

less a 15000-person invasion,

during the dead of winter, was perhaps not such a good idea. His departure left

the Bengal Army under the command of one Sir Willoughby Cotten, but by virtue of

seniority, the entire Army of the Indus now fell under Sir John Keane, the

Bombay commander. The Bombay force had sailed up the western coast of India,

intending to disembark at Karachi and join their brethren upland.

Plans called for the Army to enter Afghanistan through the Bolan pass in the

south. This was the long way around, but the Khyber Pass was much more difficult to

cross, and to get there the Army would have had to march through Sikh

territory. Singh was not overly enthusiastic about large numbers of

British and Indian soldiers tramping across his country, so he threatened to

pull out if they didn't head south. A small Sikh-British force, under the

direction of Claude Wade, did ultimately head for the Khyber, though, and would

meet back up with the rest of the column in Kabul.

So the Army marched south along the Sutlej until it joined with the Indus, in

the Baluchistan territories of the Amirs of Sind, a wholly independent area. Needless to

say, the Amirs were not pleased, but the Army took the opportunity to sack the

country and loot Hyderabad, the capital. Eventually, the Amirs relented. The

Bengal army marched south, and in March of 1839, joined forces with the

Bombay contingent. The total force now consisted of 9500 men from the Bengal

army, 5600 from the Bombay side, and about 6000 men raised for the Shah of

Shujah. There were as well over 30,000 camels, around 8000 horses, and hundreds

of oxen pulling carts.

The Army's principal weapon, besides swords and lances, was the "Brown

Bess", a muzzle-loading musket that hadn't changed since the Battle of

Waterloo a quarter of a century earlier. It was accurate to around

150 yards, and a really good man could get off two shots per minute. By

comparison, the Afghan jezail, though long and awkward to carry, was

reputedly accurate up to 800 yards, and there are reports of the Afghans picking

off sheep and horses at 600 yards with a single shot.

The officers of the Army unfortunately, left a lot to be desired. Commissions

in the British Army were still purchased instead of earned, and the educational

level of the officers was barely above that of their men, 85% of whom were

illiterate. European officers of Indian regiments were even worse, and depended

on experience gained in the field - but India had been at peace for 30 years.

The Indian officers were useless, being promoted purely by seniority and

therefore, to a man, almost all were in their late 50s or worse. They had little

or no authority, though.

What made the Army of the Indus doomed almost from the start, though, was the

remainder of the force - almost 40,000 camp followers - servants, families,

animal handlers, the ubiquitous "bazaar girls" and thousands more. Camels carried the gear and put up a tremendous din 24 hours a

day. And in those days, a British officer didn't travel light: A typical

officer carried half a dozen servants, glass, crockery and silver plate for his

table, a portable wine chest, and a bathtub. Sir Willoughby Cotten required no

less than 260 camels for his gear alone, and one other brigadier required three

camels just to haul his cigars.

|

|

On February 23, 1839, the mass of humanity and beasts started across the

scorching desert. Within

days, camels started dying left and right, through shortages of food and water.

One officer counted 20 dead animals in a space of four miles. Soon the army

spread out all across the land, suffering from raiding Beluchi tribesmen at night and interminable heat and dryness during the day. By March 11th, the

entire force was down to half-rations.

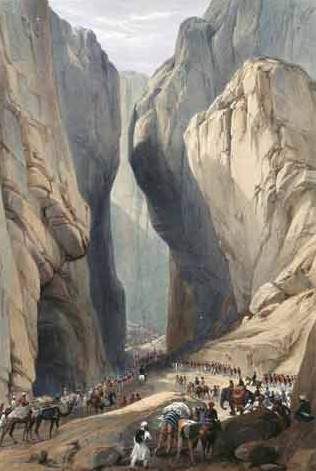

In mid-March, the force entered the southern end of the 60-mile long Bolan

Pass. The pass had walls 500 feet high on either side, no

roadway, a narrow river

running down the middle, and a pathway varying from 500 yards to less than 70

feet wide. The Beluchi's peppered the column from the heights, and the men in the

rear were not heartened to be passing the bodies of slain animals and men as

they moved forward. One officer wrote back that the force looked more like an

defeated army in retreat than advancing conquerors. either side, no

roadway, a narrow river

running down the middle, and a pathway varying from 500 yards to less than 70

feet wide. The Beluchi's peppered the column from the heights, and the men in the

rear were not heartened to be passing the bodies of slain animals and men as

they moved forward. One officer wrote back that the force looked more like an

defeated army in retreat than advancing conquerors.

Finally though,

after two long weeks, the head of the force straggled out of the northern end of the pass onto the high plain. The nearby town of

Quetta was thought "a wretched place", but there was food, water, and

acres of peach and apricot trees. By April 6th, the column was through

the pass, and General Keane had his entire army together, in one place, for the

first time.

However, the mismanagement of the supply situation was

still a problem - the troops were on half rations, and the camp followers

on quarter rations. It was so bad that even the perennially

over-optimistic and sanguine Macnaghten wrote back to Auckland "the

troops and followers are nearly in a state of mutiny for food".

Things didn't get better as the army plodded north. Water was nowhere

to be found. Beasts and men dropped by the dozens. As they approached

modern day Kandahar, the militant ones hoped for a good fight, but

Mohan Lal, Burnes' aide-de-camp, had bribed the chiefs in town with

British gold, and the city welcomed the returning Shah Shujah with a

vocal procession. The adoration of the crowd was considerably dimmed a

few days later at his 'official coronation', when a miniscule percentage

of the city's population turned out to grumble at the British force and

glower darkly at the Sikh bodyguards. Of course, the British celebrated

their successful mission at a party thrown by Burnes in which the

principal menu items were iced champagne and wine. Later, several

officers would write home that they were surprised by the total apathy

shown Shujah by the natives, and rather bewildered by the lack of

enthusiasm that they had been led to believe would occur (by Shah Shujah,

of course).

|

|

The Army was stuck in Kandahar for over two months waiting for

supplies. They waited for food, horses and military supplies to come up

from the south. Enlisted men took to looting and pillage for excitement. 40 of

them were flogged on one eventful day. The Indian sepoys turned homesick

and listless. The Afghan natives did a lively trade by stealing the

English camels at night and then selling them back the next day. The Army was stuck in Kandahar for over two months waiting for

supplies. They waited for food, horses and military supplies to come up

from the south. Enlisted men took to looting and pillage for excitement. 40 of

them were flogged on one eventful day. The Indian sepoys turned homesick

and listless. The Afghan natives did a lively trade by stealing the

English camels at night and then selling them back the next day.

Finally, though, the column turned north towards Kabul and Dost

Mohammed on June 27th, the same day old Ranjit Singh died in Lahore.

Inexplicably, General Keane decided to leave all the heavy cannons and

siege guns in Kandahar. Sniping from the heights continued to bedevil the marching

column. Occasionally Shujah's men would catch a sniper and the

retribution was swift, visible and gruesome - the stoic Afghan was tied

to the mouth of a cannon barrel and blown to pieces..

|

The fortress town of Ghazni was next in line - walls

thirty feet high, and almost as thick, surrounded by a moat, and perched on the side of a mountain.

It seemed impregnable, and Keane soon regretted leaving his large siege

artillery back in Kandahar. However, fate smiled upon the British force

for one of the few

times - a nephew of Dost Mohammed escaped out of the city and stole into

the British camp. For what amounted to around $250.00, the ever present

Mohan Lal paid him to draw up a map of the city's fortifications.

Soon the British were in possession of the fact that,

although the Kandahar gate to the city was heavily fortified and bricked

up to prevent it being blown in, the Kabul gate on the other side of the

city was not reinforced at all. The plan was hatched to move around the

city under cover of darkness, blow the Kabul gate in, and storm the city

before the defenders knew what was happening. Stupidly, however, Keane told

Macnaghten of the plan, and even more stupidly, Macnaghten told Shah Shujah,

who's babbling attendants managed to leak the news to the

locals.

|

One starlit night late in July,

(later, Sir) Henry Durand and some of engineers snuck up towards the

gate, with a wildly over-sufficient amount of gunpowder. While still 150

yards from the gate, the waiting Afghan snipers started peppering them

with shot. Somehow, Durand and the sappers managed to set several bags

of powder against the gate, all the while being shot at from above, and

even subject to rocks and mud bricks being dropped on them, most of

which found their mark. Hurriedly lighting the fuse, Durand and

the sappers high-tailed it for the moat and tossed themselves in. As

would be expected, the fuse went out. After a few moments, Durand fired

his pistol at it, but with no success. He decided to crawl back to the

gate and relight the fuse.

Meanwhile, the officer covering

the sappers decided that it had taken so long that Durand and his party

must have been killed, so he decided to charge the gate and try to blow

up the powder himself. As he got close, the gunpowder, thanks to

Durand's second try, blew up with a tremendous roar, tossing the office

several yards backwards into his troops. Amazingly, the only British

casualty of the huge explosion was the company bugler.

Chaos ensued. With no bugler,

the British troops had no way of knowing when to charge. Finally, they

advanced on the burning gate. Fighting was fierce, not in

the least because of the tremendous pile of rubble that blocked their

way. After a bloody ebb and flow during which both British and Afghan

warriors fought bravely, the Afghans were surrounded and forced to give

up arms. Nearly 1200 were killed and over a thousand taken prisoner, with

nearly 200 British and Indian casualties. The troops turned to looting,

burning and other typical cruelties. To add to the horror, fifteen

hundred Afghan horses broke loose and stampeded throughout the city's

center square until they were shot down by British gunners. For the most

part, the British treated their captives with restraint, with one

glaring exception. Shah Shujah ordered 50 of the defenders to be

beheaded. A British officer chanced upon the scene and described it with

horror to Macnaghten, telling of the captives being bound hand and

foot, men and boys alike, Shujah's executioners hacking away with their

long swords. This act of brutality towards his own countrymen did not

sit well with the British, nor would the Afghans forget it.

The strongest fortress in his kingdom having fallen, Dost Mohammed

attempted to compromise, but turned down the British offer of peaceful

exile in India. He replied that "if Shah Shujah was such a popular

ruler and the people of Afghanistan were so anxious to see him lead, why

were the British there with all their military might and power. Why not

just leave and see whom the Afghans really wanted to lead them."

His counteroffer was itself turned down by Macnaghten. The Army of

the Indus continued it's march on Kabul, about 80 miles north.

Josiah Harlan came back in to

the picture a few weeks later, ostensibly in charge of Dost Mohammed's

army, but in reality seeking employment with the British. They'd had

enough of him by now. More of a nuisance than a trouble-maker, Harlan

had started out with Singh, training his army, then moved to British

employ as a "special envoy", then over to Shujah's army, and

was now finding his position with Dost Mohammed tenuous. The exasperated

British packed him up and shipped him back to Philadelphia.

Mohammed's army came out one

more time, and, Koran in hand, he exhorted them to charge so he could

"die with honor." The response was wholesale flight by most of

his army. Dost Mohammed fled north towards Turkestan with his oldest

son, Akbar, and about 2000 loyal troops. The British entered

Kabul, pushing Shah Shujah ahead of them. His welcome into the city was

described as "restrained" by one sardonic English officer who

watched the procession. He "gleefully bounded" into the Bala

Hissar, the palace/fort/stronghold where traditional Afghan rulers

either hid from or terrorized their subjects. His 600 wives took up

residence as well. The British Army of the Indus had done its' job.

Their success due more to Mohan Lal's

knowledge and ability to pass out gold than British military power, many

officers were disappointed at the lack of action with which to advance

their careers. One officer judged most of the country through which they

had marched "totally impracticable for an army if properly defended

by the enemy".

The Army of the Indus had

achieved its' objective. Shujah was back on his throne. Auckland was

made an Earl, General Keane a peer - Lord Keane of Ghazni - Clade Wade,

in charge of Singh's army was knighted, and Macnaghten was made a

baronet. Despite logistical failures and the dismal harmony among top

officers, the Army had acquitted itself fairly well. There were

appalling losses among the camp followers, and thousands of horses and

camels had died, but Afghan resistance had proved surprisingly light.

However, the real problems lay ahead.

|

|